Zero-to-Sidekick Neural Networks: Part 1- What are they?

Published:

Detective Spooner: “Human beings have dreams. Even dogs have dreams, but no you, you are just a machine. An imitation of life. Can a robot write a symphony? Can a robot turn a canvas into a beautiful masterpiece?”

Sonny: “Can you?”

I, Robot (2004)

I, Robot has a 57% on Rotten Tomatoes. I personally enjoyed watching it, even though there can be some corny dialogue every now and then. Though many moviegoers didn’t love I, Robot, it brought up questions that we’re still asking today. In the past few years, artificial intelligence models could turn a canvas into a masterpiece, even when I cannot. I’ll admit we’re not quite at the AI causing a robot revolution phase, but I think it’s still worth trying to learn just what AI is. In this series, Zero-to-Sidekick Neural Networks, we’ll take a look into how neural networks (just one type of AI) work.

Neurons

The brain is full of these things called neurons. Neurons are cells in your brain that shoot out electric signals to other neurons, they’re how the brain performs complex functionality. Chain together billions of neurons and you’ve got yourself something akin to a human brain! Artificial neural networks (I’ll be calling them just neural networks) are composed of artificial neurons that are mathematical models of how biological neurons work, in theory.

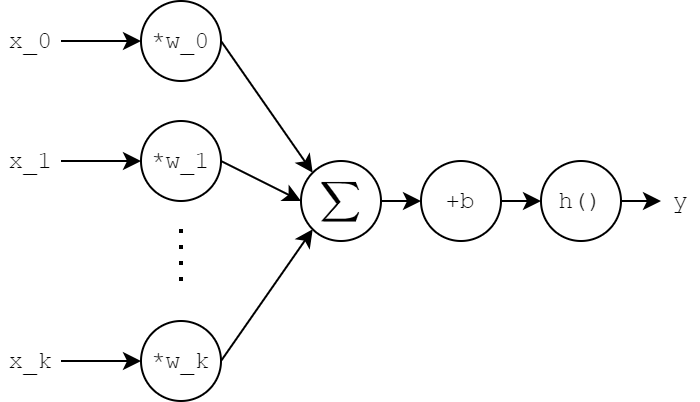

Neurons in neural networks take in any number of inputs (in this image, k+1 inputs), multiply each element of the input x_i with a corresponding weight w_i, adds up all the products, optionally adds a term called the bias (b), then applies a function h() called the activation function to produce y. Whole lot of steps, whole lot of confusion. I think it’s helpful to think about this in terms of vectors and matrices, since that’s ultimately how the computer will do. Let’s assume the following:

- The input x is a column vector composed of k+1 elements

- Weights for a neuron can also be considered as a k-dimensional row vector w

- For a single neuron, there is a single bias term, the scalar b

- h() is a function mapping a scalar to a scalar

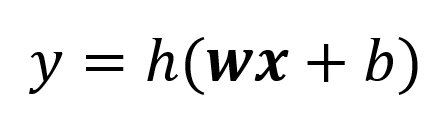

So now what do we have to represent the neuron? How about:

Elegant!

When we train a neuron (more on training in a different post), we update the weight and bias elements.

Fully Connected Layers

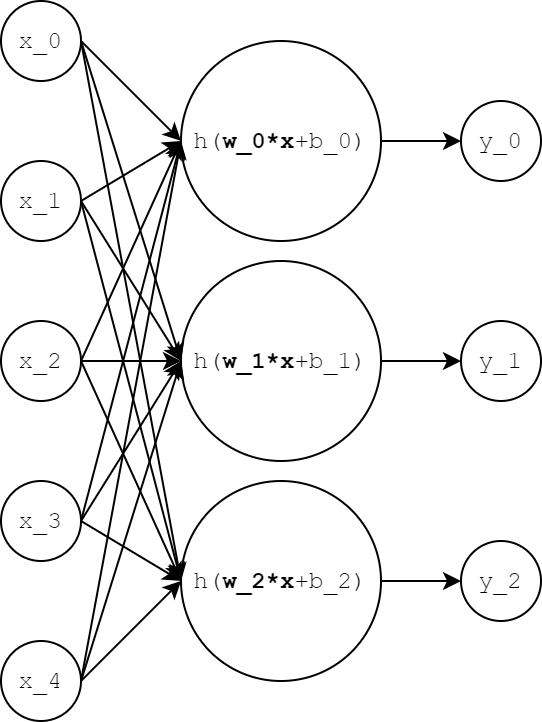

A single neuron is fine and all, but if our brain only had a single neuron, we probably wouldn’t be processing and learning much. When we have multiple neurons that all see the same input x, this group of neurons is called a layer. Since each of the neurons in a layer takes as input x, there is a full set of connections, and so we call this type of layer a fully connected layer. Here’s an example where k+1=5 and we have three neurons:

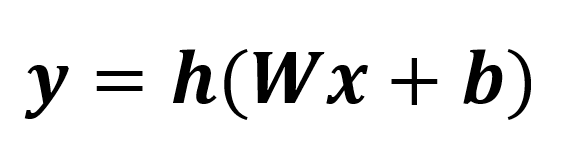

x has five dimensions and the output y has three dimensions since we have three neurons. Note that each neuron has its own weight vector w and bias b. If we keep taking our fancy math further, we can stack all the weight vectors to make a weight MATRIX W and stack all the bias terms to make the bias vector b. W will have as many rows as there are neurons in the layer and as many columns as there are elements of the input. b has as many elements there are neurons. In our formulation, b is a column vector. Thus, the entire layer looks like the following:

h() (not the un-bolded version, h()) is the activation function applied to each element of the vector Wx+b. y ends up being a column vector with as many elements as there are neurons in the layer.

Activation functions

Not yet! Let’s circle back.

Fully Connected Networks

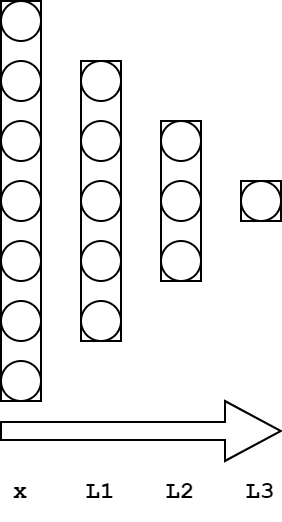

Take layers to the next level: imagine one layer leads into the next. Now we can REALLY start harnessing the power of the neurons. Our brain has neurons signaling others, just like how an artificial network can propagate one layer’s output to another. Here’s a three layer network with k+1=5, 3, 1 for each layer, respectively and the input has a size of 7:

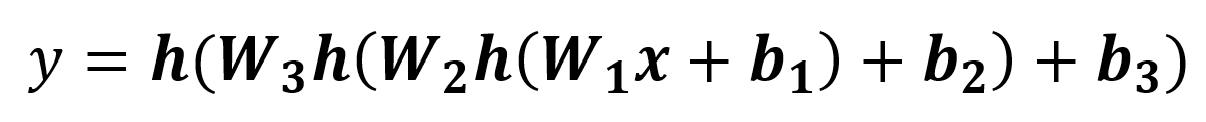

The whole network can be collapsed into one equation (where each layer L_i has set of weights W_i and bias vector b_i):

It’s all coming together! This network is taking some input x and giving some output y. We’ve just made our own very fancy function. So what’s the big idea? Why care?

Well, the end goal is for our network to predict some value y and compare it against some ground truth. Imagine we are trying to build a network that takes in seven numeric attributes of some animal (for our example, maybe: weight, height, whisker count, claw length, pupil width, paw print length, tail wags per second) and tries predict weight this animal is a domestic house cat or a lion. The input x would be these seven values and the output prediction y could be a “0” for house cat and “1” for lion. Neural networks can model many different functions, including our big/small cat classifier. The whole process of the network trying to figure out how to get the correct answer (by changing the weights and biases) is called learning. More on that in a different post.

Activation functions (actually)

What exactly is an activation function? Remember that it’s a function that maps a scalar to another scalar. But we should think about how to pick this function. Consider the activation function h(x) = x (a line with a slope of 1 and a y-intercept of 0). Our network from the previous section boils down to the following:

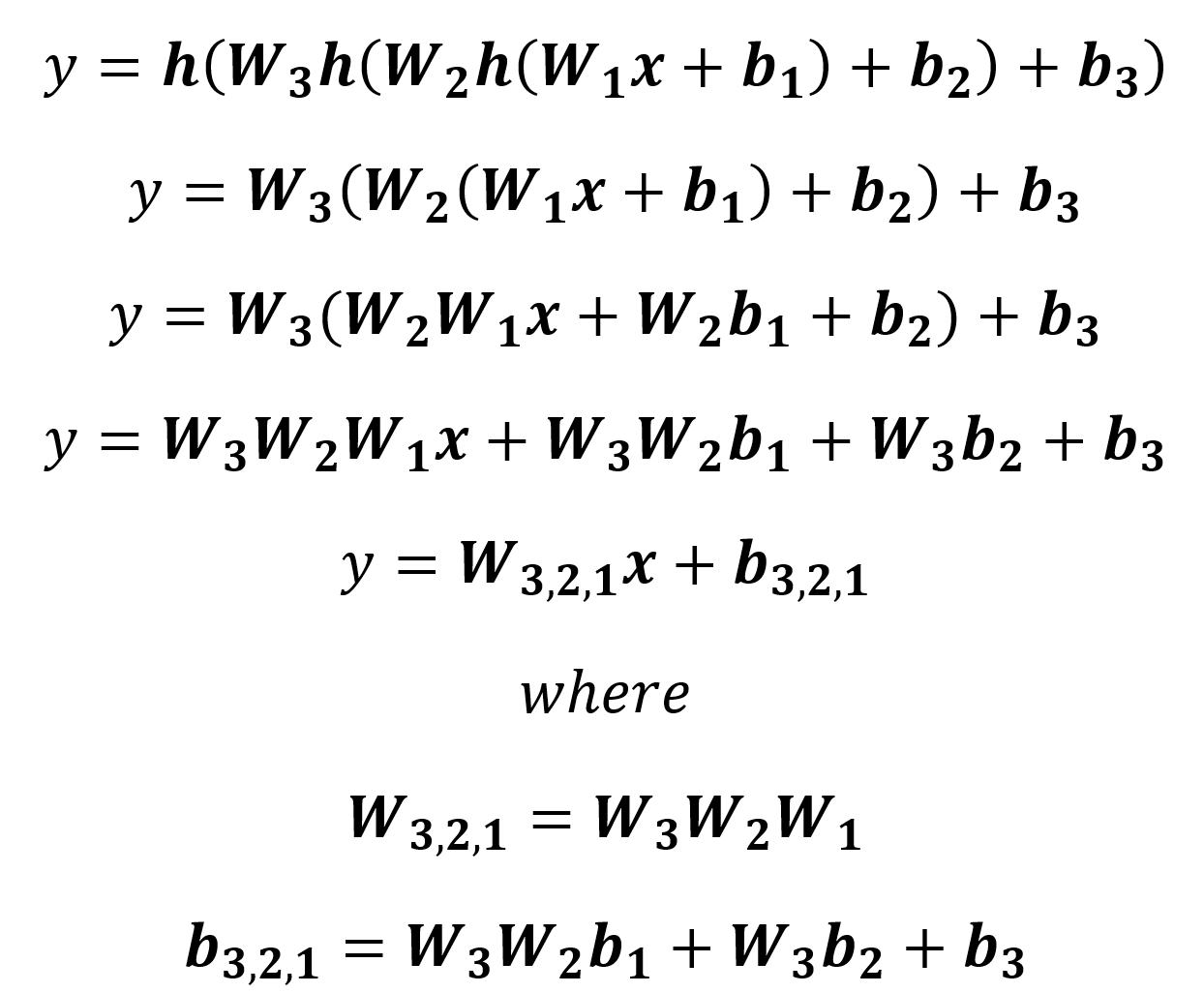

We can see that the weight matrices collapse into one matrix multiplication and one bias vector. It’s like we have just one layer. This is fine for a function that looks like this:

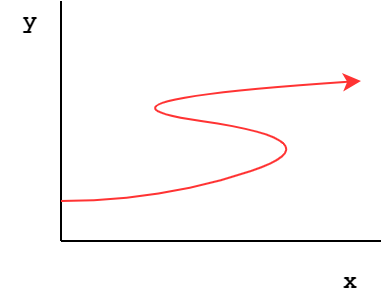

Linear functions are easy! Imagine something a little trickier though, like this:

For this reason, we need to use some nonlinear functions, like the sigmoid function or the rectified linear unit. These functions inject nonlinearity into our network so that the network can model much more complex functions. More on some of these in another post.

Wrapping Up

This is just the beginning of our process of going from zero to not-quite-hero, so be on the lookout for more. For now, let this post stew for you.